The Washington Post: “Something similar is happening to doctors, nurses and pharmacists. And when they’re hit with too much information, the result can be a health hazard… It’s called alert fatigue… Electronic health records increasingly include automated alert systems pegged to patients’ health information… The number of these pop-up messages has become unmanageable, doctors and IT experts say, because of reflecting what many experts call excessive caution, and now they are overwhelming practitioners.”

I had to laugh when I read The Washington Post article quoted above. Pharmacists have been dealing with this for years. We’ve been getting hammered with unnecessary alerts since electronic order entry became a thing. I don’t know exactly when it started, but it’s been an integral part of my career for the past 20 years.

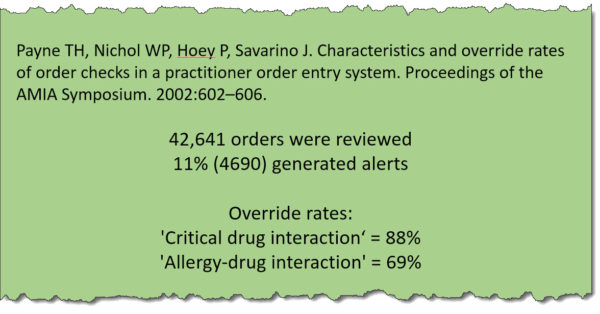

It’s a problem to be sure. A vast majority of alerts, conservatively 90%, have absolutely no bearing on the job clinicians are asked to perform. The article mentions receiving alerts for pain meds when it’s obvious that the patient needs them, such as in a post-op situation. Even more ridiculous is getting an alert for a duplicate fluid, or my favorite, lactation warnings for an 80-year-old female.

It’s difficult to say what the impact of these alerts is on patient care, but I think it’s safe to say that they cause more harm than good. They pop up so often that most simply get ignored. I know that I’ve clicked through my fair share of alerts without more than a glance.

And here’s the thing, physicians see only a fraction of the alerts seen by pharmacists. Many hospitals minimize alerts so as not to irritate physicians. We wouldn’t want to irritate physicians now, would we?

With all that said, things have improved in the past few years. Usability is on the radar of hospitals and healthcare systems. We can thank consumers for that. Healthcare workers are consumers first and their experience with software and hardware in their day-to-day lives has spilled over into healthcare. Today’s software is much better than it was a decade ago, even in the Bizzaro World of healthcare.

I can recall my experience with pharmacy information systems during the early years of my career. They were terrible, and I do mean terrible. The things were barely usable. They were often functionally rich and usably poor. It wasn’t until quite recently that pharmacy systems became more user-friendly, in part because of the introduction of EHRs.

Physicians wield a disproportionate amount of power within healthcare systems, so when they are forced to use EHRs with poorly designed user interfaces and ridiculous alerts, the vendors hear about it. The result of all that complaining has been improvements in usability. As the pharmacy system is an integral part of many EHRs, pharmacists have benefited.

I dare say that we are nowhere near the user experience of consumer products, but the improvements are nonetheless welcome. Given time, and enough physician whining, we may live to see the day when alerts are useful rather than annoying. Until then, I say to my physician brothers and sisters, welcome to my world.