I recently returned from the 2018 ASHP Midyear Clinical Meeting, i.e. “Midyear†in Anaheim, CA. This year was a bit different for me as it was the first time in many years that I attended the meeting as a regular pharmacist, i.e. not tied to a pharmacy automation company as an employee or as a consultant. As such, I had no constraints on what I could see, do, or say. It was invigorating, to say the least.

I attended several educational sessions, mostly on USP <797> and <800>. However, most of my time was spent in the exhibit hall wandering from booth to booth checking out all the cool products. It was great.

As much as it pains me to say, not a lot has changed since the last ASHP Midyear Meeting I attended in December 2016.* Many of the products and vendors were exactly as I remember them. With that said, here are a few things that caught my attention:

- The “Big 3â€: Omnicell, BD, and Swisslog all had a big presence on the exhibit hall floor. All three companies appear to be vying for pharmacy supremacy as they continue to grow and gobble up small companies. The Omnicell booth was giant and seemed to always be full. Oddly, it was the only booth I walked into where someone from the company didn’t engage me in conversation.

- IV workflow management (IVWFM): No longer a hot topic. It appears that the market is slowing as pharmacy leaders turn their attention to other things. Quite a dichotomy from what ISMP and ASHP continue to recommend, i.e. the use of technology during sterile compounding. Apparently patient safety is important, unless it’s inconvenient. Pharmacy is weird.

- Drug Diversion: Unlike IV workflow management, drug diversion was a hot topic. It seems as though everyone has a software solution to help root out those pesky diverters.

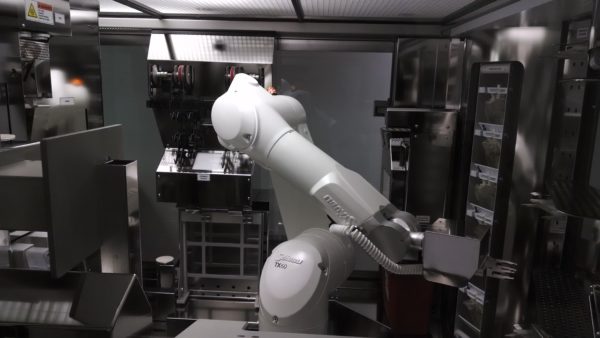

- Kiro Oncology by Grifols: I wrote about Kiro Oncology back in 2015. At that time, I didn’t think much of the product. It had some serious shortcomings, at least in my opinion. The robot lacked speed and a drug dictionary that would make it useful. Now, not so much. I was impressed with how far Grifols has come with Kiro Oncology. The speed has significantly improved and they’ve worked with their partners to build an impressive oncology drug dictionary from which sterile compounds can be made. I spent quite a bit of time speaking with a Director of Pharmacy at a facility that is using Kiro. He mirrored my thoughts, i.e. not great to start but significantly better now. Given the new focus on hazardous drug compounding, my thoughts on Kiro have changed. There is great potential here. I may write more about this later.

- PharmID: PharmID is a product that uses Raman Spectroscopy to identify drug waste. If you’ve been following my blog over the years then you know that I like Raman Spectroscopy. It makes a lot of sense when you want to know what’s in a clear fluid. Before PharmID, the company was trying to fit the technology into the sterile compounding space. That didn’t make sense to me, but this does. Given the focus on drug diversion and the inherent problems tracking waste in the OR, something like PharmID has great potential. Now all they need is something like the now defunct BD Intelliport to automatically record the volume. If you can do that — identify the drug, measure the concentration and volume — you’re all set.

- IntelliGuard: In the Summer of 2017, IntelliGuard got a new CEO and then abruptly went dark. The company disappeared from view. After visiting the IntelliGuard booth at Midyear, it was apparent why. They’ve completely revamped their image, created an entirely new marketing strategy, built some new products, improved on old products, and created an integrated platform message. I’ve always liked RFID technology for certain niches within healthcare, and IntelliGuard makes some great RFID products.

- Swisslog: Some people feel that I’ve been a little hard on Swisslog over the past couple of years. I for one, am not one of the people. I call it like I see it. And my opinion is exactly that, my opinion. When Swisslog acquired Talyst, I was skeptical. Nothing has changed, I remain skeptical. However, Swisslog has two products that I really like. The first is their analytics software. I don’t know the name of the product and can’t seem to find it on their website. Regardless, I’m impressed by the vision that the company has with the product and the number of disparate systems they’ve managed to tie into it. I would love to see it in the wild. The second product is the Relay Robot. Love that little bot. I can see so much potential.

- DrugCam: DrugCam is an IV workflow management system. I first saw the product at the ASHP Summer Meeting in Minnesota way back in 2013. DrugCam uses computer vision technology that automatically detects items and fluid volumes during the compounding process. As the user passes components in front of the cameras, the system automatically identifies them. If the system doesn’t recognize the item, the user is notified via visual cues on the screen. I’m not entirely sure how it works, but it is pretty interesting. The company had a presence in the exhibit hall but there was no hardware to look at, only a video set on a continuous loop in the background. I was really high on this technology when I first saw it. It would be good to see it in action. There’s an article from April 2016 in the International Journal of Pharmaceutics should you be interested in reading more about it.

———————————-

*I skipped the 2017 meeting due to scheduling conflicts with my new job