There’s an interesting article in the April 2014 edition of Drug Safety that looks at English Twitter posts from November 2012 through May 2013 to see if there is any correlation between adverse event (AEs) reporting via Twitter and more “official†channels.

There’s an interesting article in the April 2014 edition of Drug Safety that looks at English Twitter posts from November 2012 through May 2013 to see if there is any correlation between adverse event (AEs) reporting via Twitter and more “official†channels.

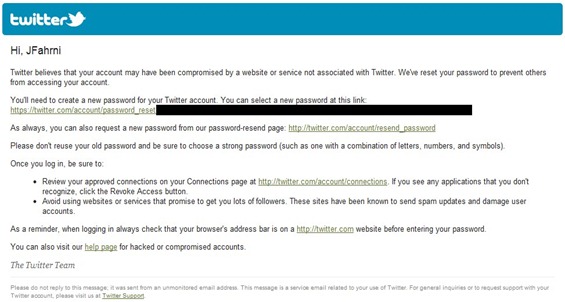

The authors collected public Tweets, which were subsequently stored for analysis using Amazon Web Services. See how they did that? Nothing magical about it. They used readily available information and a commercially available storage source.

Through the use of some human ingenuity, a “tree-based dictionary-matching algorithmâ€, and some manual labor, the authors collected 6.9 million Tweets, of which 61,402 were examined, ultimately leading to 4,401 AEs identified; referred to as Proto-AEs by the authors. During the same period 1,400 events were reported by consumers to the FDA.

While not perfect, and most certainly limited, I think the results were surprising, encouraging, and disappointing all at once.

Surprising because of the number of Proto-AEs found in the Twitter stream. People are savvy. “There was evidence that patients intend to passively report AEs in social media, as evidenced by hashtags and mentions such as #accutaneprobz and @EssureProblems. Even within 140 characters, some tweets demonstrate an understanding of basic concepts of causation in drug safety, such as alleviation of the AE after discontinuation of the drug.â€

Encouraging because being able to mine social media streams like Twitter could open up an entirely new avenue of real-time AE tracking; we all know that AEs are under reported, which leads to a lack of information for pharmacists and other healthcare professionals.

Disappointing because of the limited number of AEs reported to the FDA. I used to see AEs in the hospital that were never reported. I’m as guilty as many for not reporting AEs.

More work needs to be done in this area before we can begin to rely on data mined from social media, but they again it’s probably as reliable as information collected elsewhere.

The article is open access and the full version is online for free, so there’s no excuse not to read it.

There’s an interesting article in the

There’s an interesting article in the