“Although some hospitals have chosen to limit use of these systems [IV workflow technology] for focused areas like admixture of chemotherapy or high-alert drugs, there’s no telling when someone might accidentally introduce a high-alert drug when preparing other drug classes that wouldn’t ordinarily be scanned. Therefore, to be maximally effective, the system must be utilized for all compounded admixturesâ€. (ISMP)

A couple of weeks ago I wrote about the need to use bar-code scanning technology during compounded sterile product (CSPs) preparation. In my mind it’s a no-brainer. The i.v. room is a dangerous place, and no amount of “double checking†is going to change that.

The efficacy of i.v. medication administration hinges on the integrity of dose preparation and labeling in the pharmacy. Get it wrong in the pharmacy and you get it wrong at the bedside. Which is why I’m perplexed by pharmacies that have made a conscious choice to limit the use of i.v. room automation and technology to a small percentage of their formulary. As I continue to visit hospitals and look at the use of semi-automated i.v. workflow management systems and robotics, I am struck by how few pharmacies use these systems for all CSP production.

There’s a false belief that using these systems for high-alert medications, chemotherapy, and a randomly selected number of “dangerous medications†will somehow prevent all errors from occurring. As well-intentioned as this approach may be it fails to get to the crux of the problem, i.e. choosing the wrong item during sterile compounding.

Much effort has gone into increasing awareness around high-alert medications in acute care pharmacies. Drugs such as neuromuscular blockers, chemotherapy, concentrated electrolyte vials, and so on now contain a litany of warning labels attached to shelves, bins, and medication bags. Take a look at the ISMP high-alert medications list for acute care settings. The list incorporates a sizable chunk of medications used to treat acute illness, i.e. the medications used when people are in the hospital.

Today it’s easier to spot items that are free of warning labels than it is to determine which are more dangerous than another. Medications have been de-alphabetized, relocated, double and triple checked, and put under lock and key in an attempt to limit errors. It is unclear to me exactly what effect this has had on error reduction on the whole, but I can assure you that it makes medication distribution frustratingly more difficult. Which is why I don’t understand the failure of pharmacies to use readily available technology to limit sterile compounding errors. It’s even more perplexing when I see a pharmacy using an i.v. workflow management system – DoseEdge, BD Cato, Verification, and so on – on only a limited formulary.

There are those that will say certain medications present low risk for error, and even when an error occurs will likely not cause harm. That’s true in many cases. All errors are regrettable, but few are clinically significant. Only 2% of errors that occur during CSP production have been shown to be clinically relevant.[1]

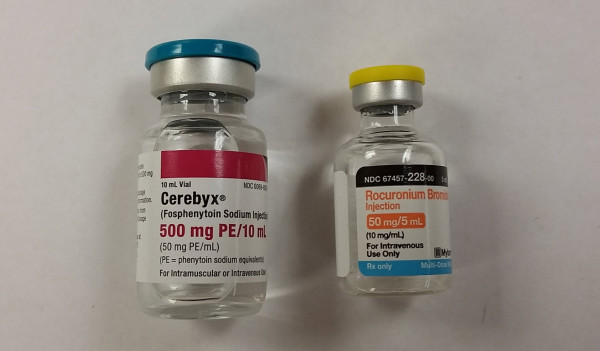

With that said, what happens when someone grabs a potentially deadly medication in place of an item that has been identified as low risk? That’s exactly what happened in the recent tragedy in Oregon. [2] The ordered medication, fosphenytoin is not considered a high-alert medication, and as such doesn’t require the use of special precautions in most facilities. The drug that was mistakenly used, rocuronium is on every high-alert medication list known to man. The items look nothing alike, as can clearly be seen in the images below. Nonetheless, the error occurred and a patient died.

Perhaps the error would have been avoided if made in reverse, i.e. order for rocuronium instead of fosphenytoin. I wager that the pharmacy involved in the error has special safeguards in place when preparing a neuromuscular infusion for a patient. Every pharmacy I’ve ever worked in has special procedures in place for preparing CSPs containing a neuromuscular blocker. Why? Because a mistake with a neuromuscular blocker can be deadly. Regardless of whether or not the reverse would have prevented the mistake, a mistake was made. Scanning the medication vial against the patient label during CSP production would have prevented the mistake, or at the very least alerted the preparer of the mistake.

It’s time for pharmacies to stop limiting the items they scan during CSP preparation. Scan it all.

————————————————

- Flynn, EA, Pearson, RE, Barker, KN. “Observational study of accuracy in compounding IV admixtures at five hospitals.â€Â Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 1997 Apr 15; 54: 904–912

- Wrong drug put in IV bag led to fatal Bend hospital error. 2015. Available at: http://www.ktvz.com/news/st-charles-to-issue-results-of-fatal-drugerror-probe/30115104. Accessed January 4, 2015.

Leave a Reply