I am currently reading an article on the use of gravimetrics in the preparation of hazardous CSPs published in the Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics.*

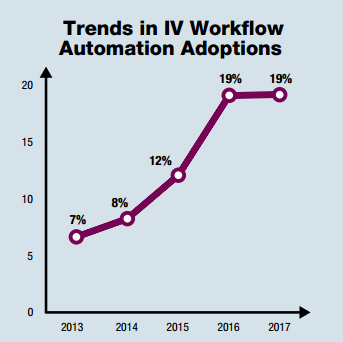

The article addresses data collected from a large-scale, retrospective analysis of medication errors identified during the preparation of antineoplastic drugs, aka chemotherapy. The paper looks at 759 060 doses prepared in 10 pharmacy services in five European countries (Austria, Czech Republic, Denmark, Germany, and Switzerland) between July 2011 and October 2015. While the sheer number of CSPs made over that period of time isn’t impressive, the fact that they’re all chemotherapy is. I believe this is the first article of its kind. I can’t think of another article that looks at the use of an IV workflow management system across such a large number of facilities, much less the use of gravimetrics during the compounding of sterile hazardous drugs.

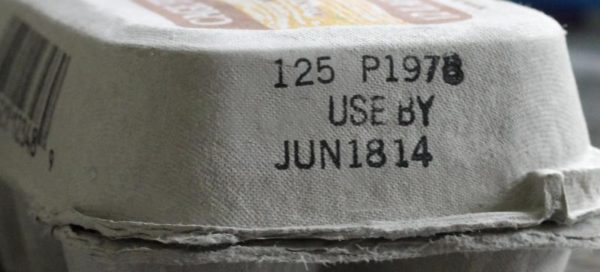

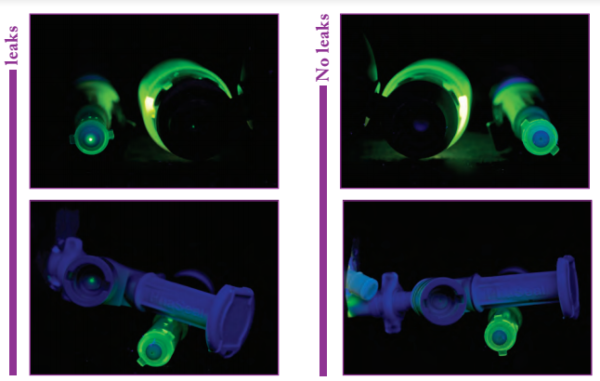

The authors of the paper do a good job of: (1) addressing the use of gravimetrics versus image-assisted volumetrics, (2) covering the weaknesses of using syringes to measure small volumes (take a look at FIGURE 2 Tolerances of 1- and 5-mL syringes), and presenting a solid case for why gravimetrics is important for preparing hazardous CSPs. It also has some good images and tables, which I plan to refer to in future presentation.

In a nutshell “[e]rrors were… identified during weighing stages of preparation of chemotherapy solutions which would not otherwise have been detected by conventional visual inspection“. I find that this is the key benefit of using a system with gravimetrics, i.e. the accuracy of the dose doesn’t rely on human inspection. Overall, the gravimetric system caught errors in 7.89% of the 759 060 antineoplastic doses prepared. This percentage is consistent with other studies looking at CSP error rates.

A total of 13 831 errors for doses that deviated by more than 10% were caught by the system. That may not sound like a lot, but it can be, depending on the situation. Worse yet, 4 467 errors were off by 20% or more. Regardless of the situation, a 20% deviation in a dose is unacceptable. The significance, of course, is that a deviation this large could result in unintended toxicity or under treatment, depending on the direction of the error, i.e. 80% – 120% of the prescribed dose.

The article concludes that the “Introduction of a gravimetric preparation system for antineoplastic agents detected and prevented dosing errors which would not have been recognized with traditional methods and could have resulted in toxicity or suboptimal therapeutic outcomes for patients undergoing anticancer treatment.” I agree in principle with the sentiment, but believe that the authors overstate the significance of the gravimetric system while understating the importance of secondary checks. By stating that the system “prevented dosing errors which would not have been recognized with traditional methods” they are assuming that all errors would have made it past a pharmacist or other secondary verification method. It’s possible — maybe even likely — that some of the errors would have made their way past a secondary check, but not all. In many cases, chemotherapy preparations go through several step-checks during the compounding process. Typically, one of those step-checks is verifying the dose — volume in the syringe — prior to injecting it into the final container. Errors are often discovered at this point in the process. With that said, the author’s overzealous conclusion shouldn’t take away from the importance of gravimetrics in preparing CSPs.

Do yourself a favor and go get a copy of the article. It’s worth a few minutes of your time.

The online article is here.

A PDF copy can be downloaded here.

——

Notes:

The system used in all the pharmacies was BD Cato.

BD funded the project. While this can raise some red flags, I don’t think it’s enough to disqualify the data. Other companies, like Baxter, sponsor half of the sessions on compounding safety at ASHP Midyear. I for one am happy they do it. Support from companies like BD and Baxter go a long way in bringing important topics like compounding safety to the masses. So, focus on the use of gravimetrics, not on the company that sponsored the paper.

*Terkola R, Czejka M, Bérubé J. Evaluation of real-time data obtained from gravimetric preparation of antineoplastic agents shows medication errors with possible critical therapeutic impact: Results of a large-scale, multicentre, multinational, retrospective study. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2017;00:1–8. https://doi/org/10.1111/jcpt.12529